A goldfish bowl in a room that "channels" melancholia is more than an eccentric antique. Fringed by long curtains and carpet giving overtones of homespun luxury, it is also flanked by Edvard Munch's haunting lithograph, Woman in Three Stages. "This is a goldfish bowl … but it also speaks volumes to me about this locked world, this sort of concept that especially women in the 19th century would have inhabited," Tan said at the press preview.

Unveiling a Forgotten Archive

Tan had been given access to the entirety of the Rijksmuseum collection and had spent two years developing an exhibition that makes hidden stories visible. Prompted by a jumbled drawer at a friend's house and a painting called Portrait of a Kleptomaniac by Théodore Géricault, Tan was fascinated with how early psychiatry sought to humanise, and not demonise, perhaps surprisingly "vibrant" patients in asylums.

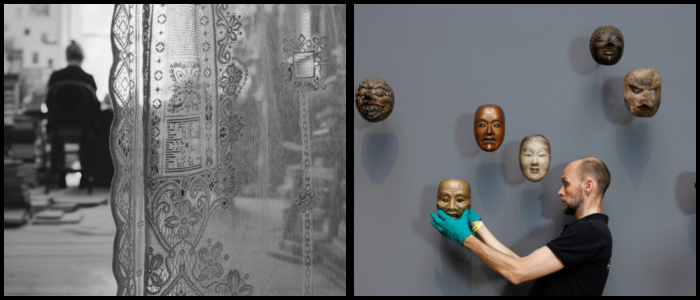

The exhibition covers 10 rooms and involves rarely exhibited things: portraits of those diagnosed with emotional disorders (in France, Austria, the UK); works by Munch; Asian masks; fragile laces; and several perturbingly exhibited christening gowns. These artefacts show shifting ideas about madness and mental disorders in the 1800s.

Some of the content comes with trigger warnings. Diagnoses from institutions such as the West Riding Asylum in York include such descriptions as "pride," "dementia", and "general paralysis of the insane". It labelled as other categories those from post-revolutionary Paris as simply "depressed"—a response that, Tan hints, was anything but abnormal.

History Made a Modern Cup of Madness

It's the first time that the Rijksmuseum admits a modern artist to directly respond to its archive. Artists such as Joan Miró have drawn on the museum's collection before, but Tan's project is remarkable for its focus on internal worlds and the history of psychiatry, said Taco Dibbits, the museum's director.

The last room of the exhibition houses an imagined audio narrative of "the criminal class," a three-screen video installation and unfinished works, such as a self-portrait of Tan masked. "Hearing voices when someone is slipping into psychosis … you are literally talking to someone who is not there," she said, connecting masks to a failure of emotional communication.

Organic Matter operates with a similar style of lived-in tactility; Tan's new video work, Janine's Room, stars a woman trapped in a cycle of endless reading and research, as piles of books stay motionless, drifted sand fills the scene, and snails crawl throughout. It's obsession at its absolute purest: quiet, relentless and chafing.

"This story isn't finished and doesn't have an ending," Tan wrote in the exhibit guide. Her project calls for a warmer take on mental illness — one based on personal context, rather than historic diagnosis. Yet the show may find an even stronger connection if it began with more personal tales for its ominous visuals to wind around.